On the 27th of May 2025 a VisionLab took place at the Rijksmuseum. In the Study Room Prints & Drawings we got the opportunity to look at several fascinating drawings and books. The day started with an exploration of several Jacques de Gheyn II (1565-1629) drawings, dating from circa 1575 to 1625. From sea urchin and mouses to studies of trees and hands, De Gheyn’s masterly use of the pen makes his studies of the natural and human world seem effortless. The drawing of the Sea Urchin (‘Zee Eeghel’) is accompanied by a text that describes its look. The text underneath the drawing is very detailed. A small part of the translation of the text is as follows: “This fish is made of umber white and black ice gray-ish, from the back it descends lighter to the belly, which is white, after the tail it is even more brown and dotted”. The team speculated on possible reasons for this text. Was it meant as an instruction for hand coloring, describing the patterns and colors in this much detail? Or was it an aid to memorize its appearance?

After De Gheyn, the team also encountered other depictions of the natural world by several artists. We saw some insect drawings by Lambert Lombard (c.1505-1566) and Pieter Holsteyn I (c.1585-1662). These drawings focused on the world of the small creatures and depicted them with much care and detail. The colorful beetles by Holsteyn were depicted with much care and detail. The color grading made the insects almost jump right of the page. The 16th-century drawings of dragonflies by Lambert Lombard were less detailed, but not less fascinating. The insects seemed to be cut from another source and pasted onto a new page, not dissimilar to the Gessner-Platter album in the Allard Pierson.

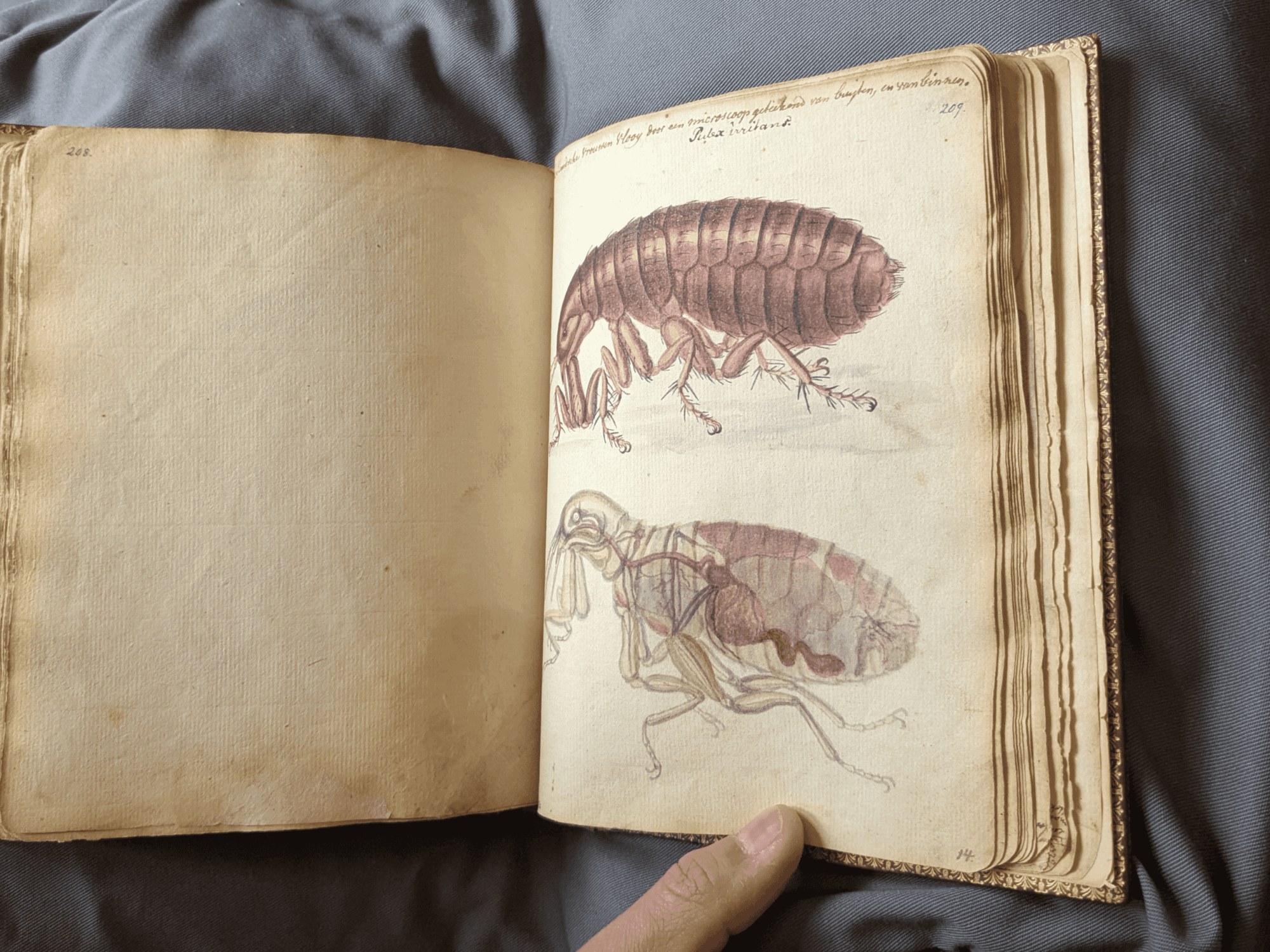

The team not only looked at drawings, but also studied some wonderful albums. While we couldn’t get our hands on the Anselmus de Boodt albums – which are currently on show in the Rijksmuseum – we did got the opportunity to take a closer look at the Tulip book of Jacob Marrel (1613/1614 – 1681) and the sketchbook of Jan Brandes. The Tulip Book (1640) contains many meticulously drawn tulips in all colors imaginable. Sometimes the colors are accompanied by insects like flies, dragonflies, wasps, butterflies and beetles. The exact function of the book is unclear; it could have been a kind of shopping catalogue where an interested buyer could pick out his selection, an inventory of tulips or maybe it functioned more like a priced possession (a kind of coffee table book, if you will). Although the Tulip Book mainly focuses on the world of tulips, Jan Brandes (1743-1808) depicted a whole range of things in his sketch book. During his stay in Batavia, Ceylon and Southern Africa, Brandes made a large number of drawings. Subjects ranged from (silhouette) portraits and depictions of plants, birds, reptiles, fish, mammals and insects to city sights and life in these parts of the world. Depicted for example is a colored overview of the binding of elephants, a table setting for dinner and a tea visit to a European house in Batavia. Described is the call of certain birds and a method on how to preserve insects. It even contained a drawing of a flea which was made aided by the microscope, as noted by the accompanying text.

The VisionLab ended with reflections on what we had seen and studied today. Seeing a range of materials, from highly detailed natural history studies in Europe to exploratory sketchbooks of nature outside Europe, revealed the diversity of approached to represent the ‘unknown’. The team experienced once again how albums and drawings could function as tools for memory, documentation and display. These insights will enrich our ongoing work at the Visualizing the Unknown project.

On a personal level, the VisionLab also allowed the author to build an internal visual library that will be essential for my internship within the project. Handling and discussing materials provided me a deeper understanding of technique, materiality and intentions that digital images and single study can not offer. This VisionLab allowed me not only to be welcomed within my new research group for the upcoming six months, but also to situate my upcoming research (the Gessner-Platter album and micro before the microscope) within a broader framework of early modern practices of observing and engaging with the natural world. Engaging with the team’s diverse perspectives made the session especially fruitful, and reinforced how collaborative close-looking can open up new questions and interpretative possibilities.