By Eric Jorink.

Welcome to our website, and the first blog of this wonderful project. In this place, we will keep you updated on our most recent findings, research and thoughts. Having started a year ago, the project is already in full swing – including what is perhaps the most exciting part of it: looking through original seventeenth-century microscopes (see MicroLabs). In trying to make sense of what we can see through these lenses and stumbling upon unexpected problems, flaws, unresolved questions, and many other issues that are not textually documented, we are very much knowing by doing. On a monthly basis we will give you an update – including photographs of strange-looking creatures and archival doodles.

But for now, it might be worth devoting a few words to the backgrounds of this international project. Hosted by three institutions, and funded by a competitive NWO Open Grant, our research brings together an exciting group of scholars and artists sharing the same interests. Elaborating on previous research on the history of optics, the visual culture of the early Royal Society, and art and science in the Dutch Republic, Sietske Fransen, Tiemen Cocquyt and yours truly had a coffee on a dark and cold day in November 2019. Two months earlier, there had been a spectacular pilot-study in Leiden, bringing together original Leeuwenhoek-microscopes from the Boerhaave collection and some preparations now at the Royal Society which Leeuwenhoek had sent to London. Efforts were made to duplicate Leeuwenhoek’s observations, and microphotographer Wim van Egmond made stunning images and movies of what could be seen through the original lenses. In the wake of the increasingly overlapping fields of art history and the history of science, and the collaboration between the academic world and institutions for cultural heritage, the results of Leeuwenhoek-pilot cried out for a follow-up.

Thus we had more coffee, and reasoned that just focusing on Leeuwenhoek might be too narrow a perspective. Why not look at the bigger picture? Why not taking the entire field of early microscopical observations into account – including lesser known figures? Although Leeuwenhoek was successful in fashioning himself as a relative outsider, it is clear that he was in constant conversation with people like Robert Hooke, Johannes Swammerdam, and Christiaan Huygens (who was – as most people are not aware – a gifted lens-grinder and microscopist himself). And how did these English and Dutch pioneers communicate with their productive colleagues in Italy? Our basic idea was to study the processes of observation, visualization and scientific communication from a broad, international perspective. How – did we ask ourselves – did our protagonists made sense of the alien world they saw through their lenses? And how did they convince their audience – also taking into account that the rise of the microscope went hand-in-hand with the establishment of the first, and lavishly illustrated, scientific journals?

Our research questions driven by our experience, curiosity and an awareness of the high scientific relevance led to a proposal – supported by all members of our advisory board – which was submitted with NWO (the Dutch national research council). We were convinced both of the intrinsic quality as well as the proposed output – including exhibitions, papers, books, lectures, a TV-documentary and, of course, a website featuring Wim’s amazing visual material.

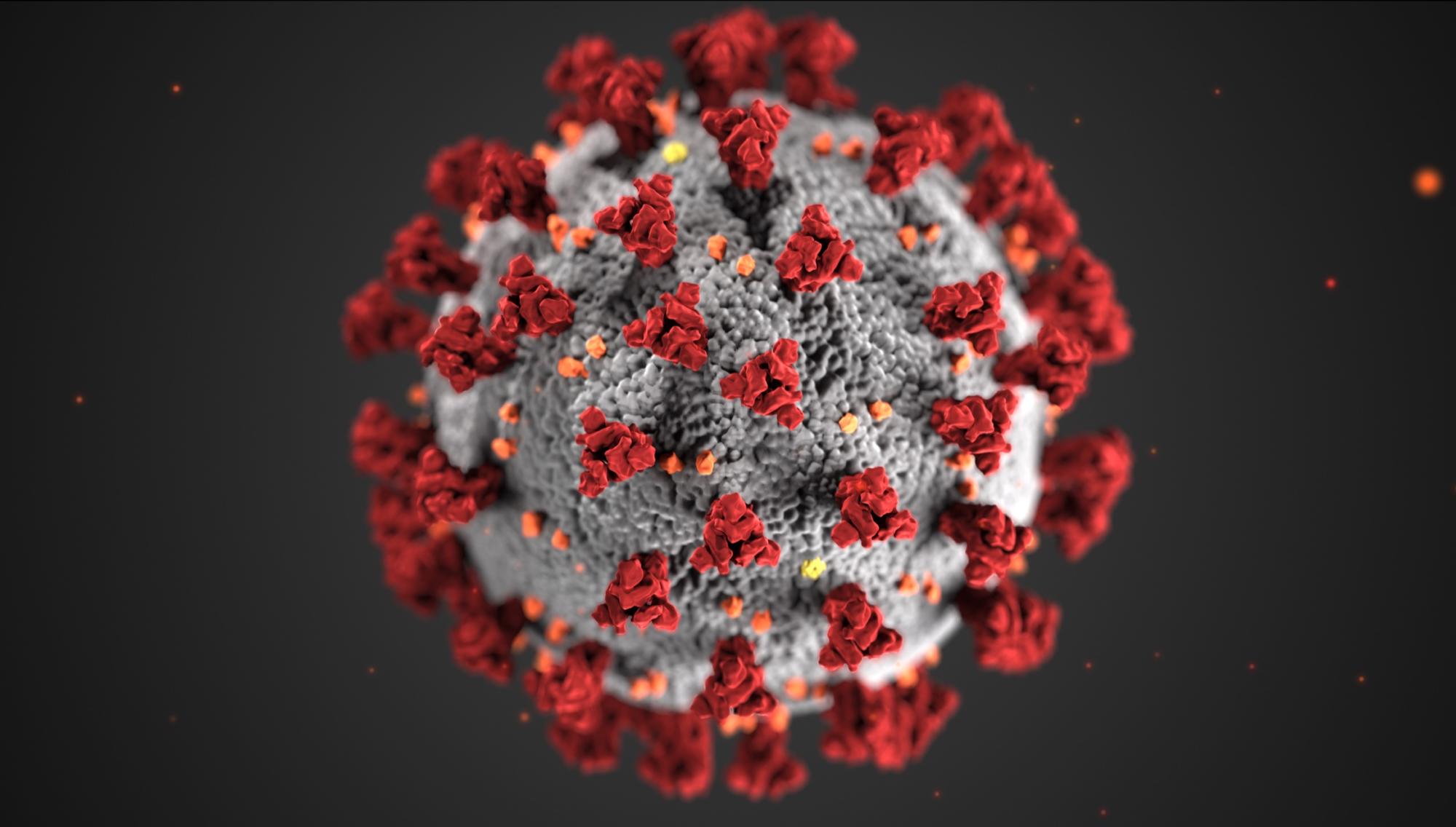

And then, in January 2020, there was Covid. Within weeks, the virus had a name (SARS-CoV-2) and a ‘face’ – the immediately iconic ‘spiky blob’-image created by the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in the USA. As the institution stated: ‘We rely on illustrations to help clarify the message, break up the content and enhance comprehension’. This visual representation anticipated even the most rudimentary knowledge of the virus. Two biomedical artists, Alissa Eckert and Dan Higgins, were instructed to use a microscopic close-up of the virus and to manipulate it with artistic means, so it could serve in public awareness campaigns, ‘bringing the unseeable into view’.

Coronavirus knit hat, March 2020 © Victoria Light.

We are extremely happy to have found an highly talented PhD-student, Ellen Pater, who not only obtained a MA in art history with a wonderful thesis on seventeenth-century Italian anatomical models, but before that graduated from art school. In the future, you will see and read more of her on this place. Moreover, from day one of our first MicroLab in Sepetember 2021, Hans Huijbrechts and Frans Van Campen proved to be of extreme importance. Nearly completely written out of the history of science, and seldom mentioned by our protagonists, the skillful art of dissecting, making preparations, finding the right source of light, appeared to be of crucial for making observations – and constructing images. Starting up the project, we were joined by our brilliant intern, MA-student of the history of the book, Larissa van Vianen.

Our project is about unraveling these successful and century-old visual strategies, and as you might learn from following our website and this blog, there is still very much we do not know or understand yet. So far our MicroLabs have demonstrated that the process of preparing objects for observation (making the microscopic preparations) is usually completely overlooked; that observations can be biased by pre-conceived notions, and that images of – for example the eye of a bee – are the composite result of dozens of dissections and copy-and-pasting separate drawings. Things are not what they might seem at first sight – and we are happy to keep you updated on our findings, thoughts and observations in the coming years.

MicroLab 2: the silkworm. A dissected specimen is seen through an original Campani-microscope, and the view is projected on the flatscreen. Photograph by Geertje Dekkers.